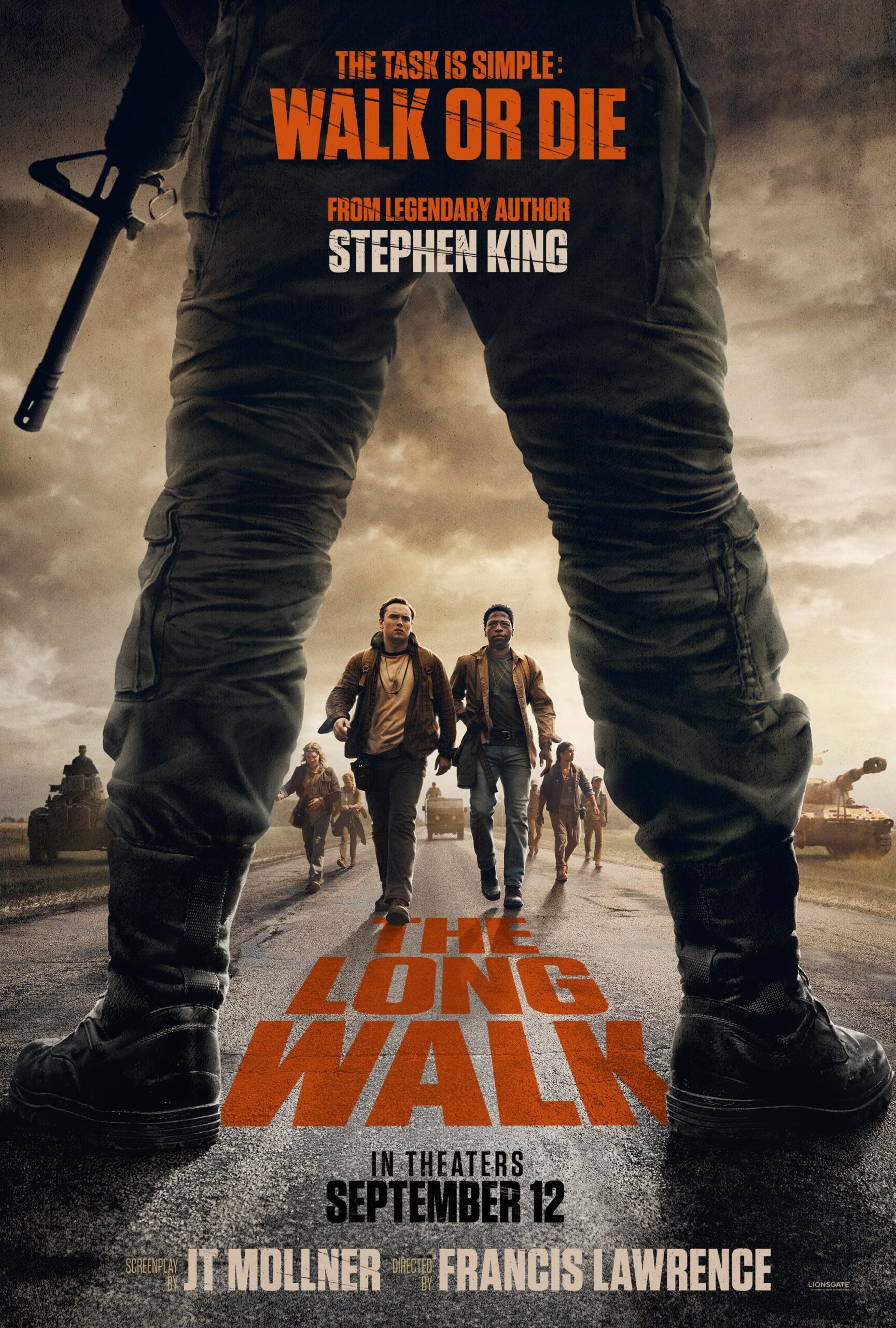

There are films that entertain, films that thrill, and then there are those that leave a permanent imprint on your soul, leaving you in a state of quiet shock as the credits roll. The cinematic adaptation of Stephen King’s early novel, “The Long Walk,”—whether the long-gestating feature film or the recently acclaimed limited series—firmly belongs to the latter category. It’s a brutal, relentless, and profoundly moving story that poses a deceptively simple question: Is this ultimately a tale of human connection, or one of utter despair?

The answer, in its devastating brilliance, is that it is both, inseparably and powerfully so.

The Premise: A Dystopian Engine of Despair

For the uninitiated, The Long Walk is set in an alternate, totalitarian America where every year, one hundred teenage boys participate in a nationally televised event called “The Long Walk.” The rules are simple, and their simplicity is the source of the horror:

- Walk at a pace of 4 miles per hour or faster.

- Stop for any reason, or fall below the speed, and you receive a warning.

- Three warnings in a row without speeding up? You get “ticketed.”

- And being “ticketed” means being shot dead by the soldiers in the accompanying half-tracks.

The last boy walking wins the ultimate “Prize”: anything he wants for the rest of his life. It’s a high-concept nightmare that serves as a pristine allegory for the mechanics of oppression, the spectacle of violence as entertainment, and the senseless sacrifice of youth.

The Heartbeat in the Horror: Garraty and McVries

At its core, any successful adaptation of The Long Walk lives or dies by its central relationship: that of the everyman protagonist Ray Garraty and the cynical, scarred Peter McVries. This is where the film finds its soul.

Their friendship is not one of easy camaraderie but a tether to humanity in a world designed to strip it away. McVries, with a facial scar that mirrors his internal wounds, becomes Garraty’s protector and confessor. He is the one who physically pulls Garraty along during a panic attack and verbally grounds him when despair sets in.

On screen, this dynamic is electric. The camera lingers on their shared glances, the quiet conversations that happen amidst the chaos, the unspoken agreement that they will face the madness together. They form the nucleus of a fragile, temporary community—the “Musketeers”—with other walkers like the gentle Art Baker. These moments of shared laughter and vulnerability are the film’s most poignant. They give us something to cling to, making the inevitable, grueling losses of these well-drawn characters not just plot points, but genuine heartbreaks.

This is the film’s central argument: friendship is the ultimate act of rebellion in a system built on isolation and ruthless competition.

The Machinery of Tragedy: More Than Just Death

However, to view this story solely through the lens of friendship is to miss half of its devastating power. The Long Walk is a tragedy in the most classical sense, and its tragedy operates on multiple levels.

- Systemic Tragedy: The Walk is a perfect, cruel machine. It’s an allegory that resonates deeply with modern audiences familiar with franchises like The Hunger Games and Squid Game. It reflects a society that consumes human suffering as entertainment, with the cheering crowds becoming a chilling Greek chorus complicit in the slaughter. The enigmatic Major, the figurehead of the regime, represents a distant, uncaring god who offers a hollow prize for an unimaginable cost.

- The Tragedy of the “Prize”: The true genius of the story is its understanding that winning is the greatest tragedy of all. The film’s final act is a masterclass in psychological horror. As Garraty, the sole survivor, stumbles forward, he is physically alive but spiritually and mentally annihilated. The ambiguous final shots—whether he hallucinates a dark figure and finds a burst of insane energy, or simply continues his endless, broken shuffle—confirm that there is no victory here. The Prize is a lifetime of trauma. The system doesn’t create heroes; it creates ghosts.

The Final Verdict: An Indivisible Duality

So, is it a tale of friendship or a tale of tragedy? It is powerfully and inseparably both.

The friendship between Garraty and McVries is so profoundly affecting because it exists within a crucible of certain doom. Their loyalty is what makes the surrounding brutality so devastating to watch. Conversely, the oppressive, tragic nature of the Walk is what gives their bond its immense significance. The film argues that human connection is the only meaningful response to a cruel world, while simultaneously acknowledging that such connection may not be enough to save you.

This is not a comfortable film. It is a grueling, emotionally draining, and philosophically challenging experience. But it is also a masterful one. It transcends its dystopian trappings to ask fundamental questions about endurance, solidarity, and the cost of survival. It’s a film that will leave you in a state of awe at its execution, and in a state of shock at the haunting, beautiful tragedy it portrays.

Long after it’s over, you’ll still feel the pounding of the pavement.

| Overall | Direction | Performances | Script | Emotional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ★★★★½ | ★★★★★ | ★★★★★ | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★★ |

“A harrowing and humane masterpiece of dystopian cinema.”